10 Questions With… Michael Kostow

Michael Kostow has spent the last three decades finding creative solutions for creative environments. He earned a bachelor’s in architecture from Lehigh University and a master’s in architecture from Yale University before joining the iconic Kohn Pedersen Fox. Going out on his own, he quickly joined forces with Jane Greenwood to found Kostow Greenwood Architects, a firm beloved for their thoughtful workplace designs for theater, performance, and media communities.

Here, in a conversation that has been condensed and edited for clarity, Kostow Zooms with Interior Design to talk about his career, the importance of behind-the-scenes spaces in the theater, and what’s next for his storied career.

Interior Design: Let’s start at the beginning. Why did you decide to study architecture?

Michael Kostow: When I started college, I didn’t know what I wanted to do, I had no preconception. Freshmen year, I took architectural history as an elective and really enjoyed it. Not only that, I met a bunch of people that I connected with. They were all architecture majors, and they said I should take a design course, since I had done technical drawing and wood shop in high school. The next year, I did and I was good with it. I decided architecture would be a good pursuit. When I got out of undergraduate, I immediately applied for graduate school and went straight into it. I did an internship in New York, then moved there and started looking for a job.

My first job was at Kohn Pedersen Fox. Bill Pedersen hired me and they were, like, 50 people [at the time]. When I left seven years later, they were over 300 people. I was there during an explosive time in the ’80s. Gene [Kohn] was just a powerhouse, bringing in work as fast as he could get it. And as fast as he could bring in work, we were doing it. It was a very different time: Postmodernism was very strong, and the work was influenced by historical styles and moods. I ended up learning a lot about classical architecture. And then, suddenly, the light switch turned off, and nobody wanted Postmodernism anymore.

ID: Why do you think that was?

MK: It’s easy to look back and kind of make fun of Postmodernism, but there were a lot of good architects practicing in that mode. I think it just became too stylized and too outrageous. And then everybody started using CAD, and it was easier to just draw straight lines, you know. (Laughs.)

ID: When did you go out on your own, and when did Jane join?

MK: In 1987, and we were pretty lucky—out of the box, we got a lot of big projects, and within a few years we’d grown to about 20 people. Mostly, we were doing work with developers. But then there was the recession in 1993, that really hammered us. So we shifted our focus towards historic preservation and interiors, because there was no new building work. Jane joined shortly after that, and we kind of powered through. We had a couple of good projects that won Preservation Awards. Without sounding corny, with Jane, it’s kind of like a marriage: you commit to it, you share values and direction. I don’t think we’ve ever had a dispute over the work or what we should be doing. We split responsibilities and we each work on projects.

ID: Let’s talk about those projects. What was the first preservation project you did?

MK: The first landmark one was 109 Prince Street, which is a beautiful building in SoHo, on the corner of Greene Street. Typical of the day, it was being used as a warehouse, storing fabric or something. The family decided to sell it for $3 million, which was an unheard of amount of money at that time. And we renovated it for another $3 million, which was also unheard of. Now, I’m sure it’s probably worth $100 million.

It was cast iron, from around the turn of the century, and it was just rundown. Pieces were falling off the façade. The windows were falling out. It needed a sprinkler system. So it was pretty much gutting the building and rebuilding it. We had to do a special filing to get through the Landmarks Commission and get retail approved. It was our real introduction to working with the Landmarks [Commission,] presenting to them and understanding their needs. It was a great project for us.

ID: Was the Longacre Theatre on Broadway in a similar state when you renovated it?

MK: Those theaters were all antiquated or had been badly renovated over the years—like they just painted everything gray, or tore out the historic elements to put air conditioning in, things like that. So restoring them is about researching what was originally there, doing forensic architecture and analyzing the layers of paint to see what the original colors were. You can style it to a period of time and recreate that but also have the modern amenities. In most theaters now the modern amenities need to be toilets. We always joke: didn’t they go to the bathroom? In a way, they didn’t—they didn’t drink and eat as much in the theater. Also, way back, women didn’t go to the theater much, only men did. So most theaters had very few women’s rooms. Renovating the Longacre, we found space to excavate under the house to add more bathrooms. We expanded the lounges, because that’s where they sell wine and drinks at intermission and make money that helps theaters viable and economical. And now we’re finishing a project for the Apollo Theater, expanding its reach into the building next door. We’re doing two new black box theaters, which will allow them to do smaller productions, longer runs, and partner with community members like the Classical Theatre of Harlem, who will be doing presentations in the space. That was a project where the developer really just built a concrete shell, a floor and ceiling and walls, and we did all the interior work.

ID: Does being a jazz musician give you a different understanding of how to design a space for those who perform it?

MK: It helps in designing backstage areas. People come in with road boxes and need wardrobe areas to be big; theater actors often won’t ask for room, they just say, give me space and I’ll figure it out. When you give them something that’s, you know, normal, they’re so happy! An 8-by-10 foot dressing room is unheard of. To get a 2-by-3 foot dressing room, you thank your stars. In music venues, acoustics are definitely important. Older theaters generally are pretty good acoustically, so if you restore it to what it was, you don’t need to do much. But in a newer space, you definitely need to focus on that.

The ornate ornamentation in older theaters acted like acoustic diffusers. You want rooms with irregular shapes and surfaces that are not reflective, to break up the sound waves. When I say newer spaces, I mean when you’re taking a vanilla shell and there’s nothing in there, and I’m trying to make a theater out of it. There are isolation issues: you don’t want the neighbors to hear it and you don’t want to hear what the neighbors are doing.

ID: Acoustic isolation was also an issue in designing the Mad River Post workplace in Dallas, right?

MK: Right, because it was a post-production company, big in the early 2000s. We did a bunch of offices for them. They found this really cool building in the cool part of Dallas, a pre-WWI munitions warehouse. The floors were planks of wood a foot thick. It was an amazing building but nobody could figure out what to do with it. The client had the courage to take it on. We built edit rooms, like little small buildings inside of the bigger warehouse, and we used a lot of industrial materials like corrugated aluminum siding, which at the time was kind of radical. The owner of the company was a collector of Mid-Century Modern furniture, and he bought all the stuff for the office on eBay. The space was so big that people rode bicycles around inside. They had great parties there. The private offices were built with latticework and ceilings of sailcloth. Of course, then all the production companies and ad agencies brought post-production in house. But that was a fun one.

ID: How did you come to design Matthew Marks Gallery in Chelsea?

MK: It came through a contractor. They had bought this building on 24th street when the center of the gallery scene was still in SoHo. They were one of the first to move to Chelsea. They were tired of paying rent in SoHo and bought a building cheap. It was a garage, and we had to do a lot of work to it. But the real design was the glass garage doors. There were no doors along that side, it was all bricked up, but they wanted it to be open to the street. They also represented Richard Serra, and so they needed to be able to drive a truck into the space and bring in like a 200 ton-sculpture. Now, that whole block is a center of the art world, but at the time there were only one or two galleries over there.

ID: Sort of like when Brooklyn Tabernacle decided to try to unify multiple buildings into a single campus—it was an act of faith?

MK: One of my partners had been the Tabernacle’s architect for their original building on Flatbush Avenue. They came to us and said: we’re buying this old theater and we want to turn it into a church. It was Thomas Lamb’s 1918 Loew’s Metropolitan Theatre. Lamb was an iconic, prolific theater architect in his period. And I mean, this place was literally falling apart. The roof had leaked for like five years, and there was mold on everything. Pigeons lived there. But the Tabernacle wanted to save it. They loved the old architecture and were committed to restoring it. We ended up using the buildings around it to create a whole campus. But in phase one, I asked the pastor, you know, do you have the money to do this? And he said, Jesus will provide. It ended up being a $40 million project, and they got a couple small loans, but most of it they came up with on their own fundraising. I was impressed!

ID: What’s next for you?

MK: Well, I’m half Italian. Over the years, I’ve reconnected with my family in Italy. They own a winery in Tortoreto, in Abruzzo. I was on a trip there having a tour, and they pointed to an old building and said: oh, we’re going to build a small hotel there, for when people come to tastings and when buyers come to entertain them. I said: why don’t you let me design it? And they said of course. I showed them seven schemes and they liked one that was one building and entertainment space. It was slated to start construction in the spring of 2020 and got stopped by the pandemic. But they will build it next year. The vineyard is on hillside that goes down to the Adriatic Sea. The view from the rooms is just down a big hill into the ends of the ocean. It’s dreamland for when I’m ready to retire (laughs).

read more

Projects

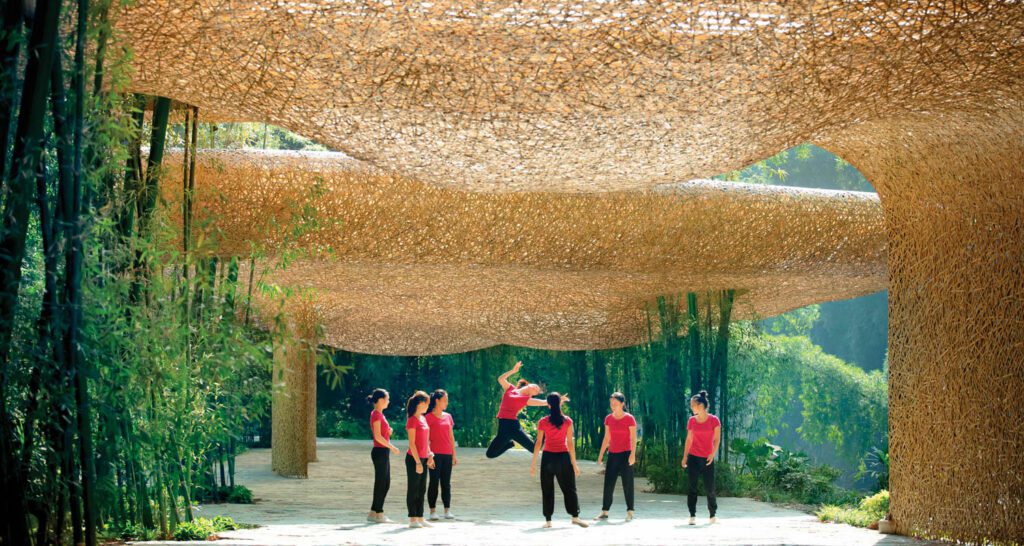

LLLab’s Locally Sourced Bamboo Pavilions in China Take Home a Best of Year Award

Chief designer Hanxiao Liu and his team at LLLab. were commissioned to provide shelter for audiences waiting between the entry pagoda and the stage, which lie at opposite ends of the island, for the 600-person musical Im…

Projects

Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates Earns an Iconic New Classic Best of Year Award

2021 Best of Year winner for Iconic New Classic. It was no small feat to conceive what would be the tallest office tower in Midtown on a site right next to a diminutive landmark—especially when that landmark is the bel…

Projects

One Plus Partnership Conceives a Seven-Screen Cinema Complex in Shenzhen, China

2021 Best of Year winner for Entertainment. It was the stage in its multiple aspects—a space for actors and performers, a focal point for audiences, and, above all, a mise-end-scène to be lit—that co-design director…

recent stories

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Louis Durot

French artist and chemist Louis Durot talks about the evolution of his whimsical forms, his upcoming autobiography, and advice from a brief run-in with Picasso.

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Jessica Helgerson

Jessica Helgerson discusses her new lighting collection with Roll & Hill, some favorite projects, opening a Paris branch of her eponymous firm, and more.

DesignWire

10 Questions With…. Tadashi Kawamata

Get to know Japanese artist Tadashi Kawamata who created a surreal installation for the facade of French design firm Liaigre’s Paris mansion in the fall.